The Right to Stay Home (Dark Mountain)

What Becomes of the People And Places Migrants 'Leave Behind?' Dispatches from Macedonia and Mexico

As I mark another movement around the old man, I’d like to offer you a little gift - an essay of mine that was recently published in Dark Mountain Issue #25 (2024). Please consider supporting the DM Project by purchasing a copy and laying your eyes on other provocative offerings. You can do so here.

Cradled by the darkness of a jungle canyon in southern Mexico, in a Chinantec village, under a makeshift tarp, sit a couple dozen men, drinking and gossiping. They are the second generation of a new kind of local, belonging to a category not uncommon in places like this: los retornados, or the recently deported.

One of them, a cacao farmer and friend who I’ve worked with over the last few years, insists that I join him. As night descends, he explains his story to me for the first time. Not unlike other young men in his village, he left at the age of eighteen to make the journey north, passing through desert and danger, to cross an invisible line into Los Estados Unidos. Over the next decade he settled there, working alongside other men from his village in a carpentry factory. Eventual bad breaks and bad decisions led him into the hands of the law and subsequently back into the village that raised him. Tonight, as his clarity wanes and the spirits of lethargy take hold, he pauses, this time raising his head instead of his glass, and asks, ‘Do you think you could help me get work in Canada?’

Now, there can be subtle and sometimes spectral moments in one’s life when memory appears in ways that supersede the clock, the cause-and-effect, and the history books. A kind of disassociation more intimately understood as visitation. This is one of those moments.

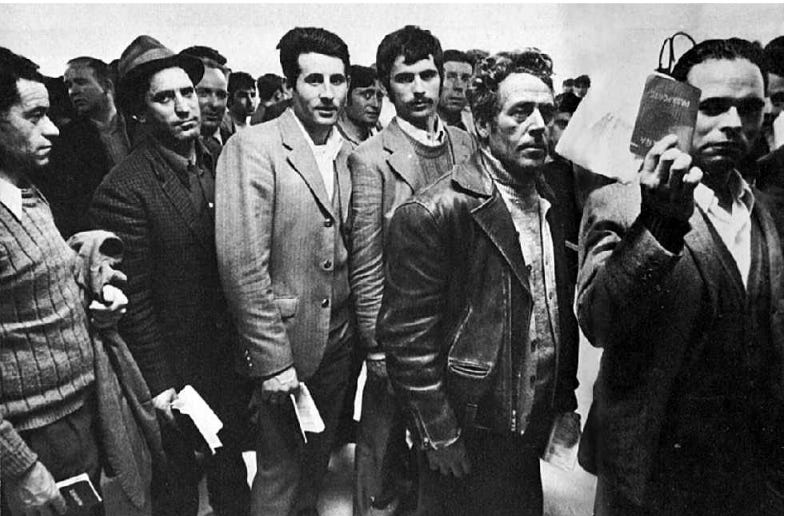

A century ago, my pra-dedo (great-grandfather) Stavros, then a youth, set out from his farming village in Aegean Macedonia in search of a better life for his family. After 500 years of rule in the Balkans, the Ottoman Empire had collapsed. As is the case with countless empires, it left in its wake a scorched-earth power vacuum that produced extreme poverty and ethnic persecution.

He left to work in boomtown Detroit. Betrayed by an in-law, he was arrested and sent back across the Atlantic. He tried again in the factories of France, where his arm was broken, and with it, any value he might have had to the foremen. Again, he was forced home. Despite the decades of endless war, constant hunger and state oppression that followed, his son – my dedo (grandfather) – finished what his father began, finding a new home for us in Toronto.

I remember: setting out for that very village 50 years after my father had left. Raised on the glory stories of the Old Country, I expected to encounter our people in their Sunday best, the scent of ancestral sustenance, and my dedo’s dialect, all rolling out the red carpet. And yet all I saw were abandoned houses, overgrown cemeteries, shuttered churches, and a single, solitary elder walking his cowherd through an otherwise empty village.

Now, facing my Chinantec friend in this remote Oaxacan village, sensing the weight and inheritance of my travels and those of my family before me, wondering what his family will do without him, I fall silent. What if the already uncertain health of this village hinges on how I respond? What if it tilts the scales towards a scattering of bones already endured by countless others?

Instead of an answer, all I’m left with is questions: what do our migrations do to those who never leave home, to those who ‘stay behind’? What does the emptying of a village do to culture, language and lineage? How can one be responsible for a place by being elsewhere? How do we contend with what John Berger calls ‘the century of departure, of migration, of exodus, of disappearance: the century of people helplessly seeing others, who were close to them, disappear over the horizon’ – the century that refuses to end?

What A Better Life Conceals

In Oaxaca, I’ve had the good fortune and honour to work alongside peasant farmers in remote villages. Together we collaborate on agroecological projects that regenerate cacao, coffee and countless other plant beings in the local forest gardens. My companeros’ hospitality, their willingness to invite a stranger into their homes, to feed and house him for a time, constantly reminds me of my Macedonian grandparents’ generosity. But that isn’t the only connection. My grandparents were immigrants in Canada, fleeing poverty and persecution. Their story seems to be shared by many in these villages, by people not unlike my dedo and pra-dedo.

The first wave of these migrations from Mexico began in the 1950s with the bracero programmes, which allowed Mexican men to work legally in the United States to harvest produce. In subsequent decades, microindustries were set up north of the border that encouraged cheap labour and illegal migration. Without papers, migrants were stuck in legal limbo, leaving them little choice but to settle indefinitely. Any return to the village meant another pricey and precarious trip north through narco-controlled territories with no guarantee of making it beyond the border. And so they stayed, sometimes for decades, sometimes for the rest of their lives, never seeing their homelands again.

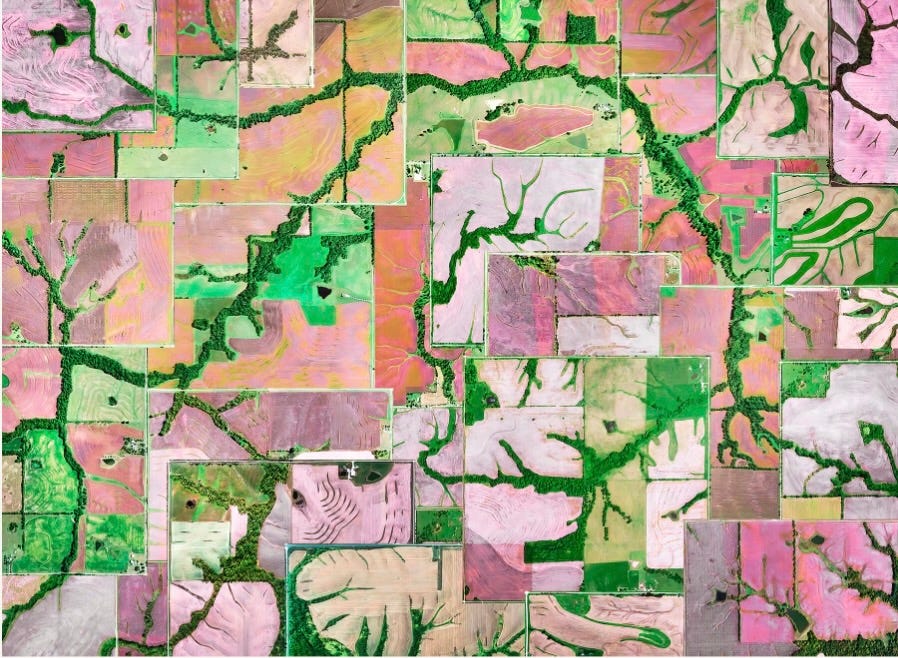

In the 1990s, the tide of northward migration became a torrent. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) flooded Mexican markets and villages with cheap American genetically modified corn, meaning the heirloom varietals that peasants produced and relied on as their main crop (not to mention the work that was put into raising them) plummeted in value. The milpa fields, which have stood as the centre of local sustenance for thousands of years, sat fallow. The already incendiary insecurity increased, and many more people left town, heading north.

Some 30 years after NAFTA’s signing, at least one third of Oaxacans now live in the United States. In the villages I visit, the result is striking. Almost all of the farmers I work with are grandparents and elders, getting by with the help of the younger women and grandchildren. We can wonder about the long-term consequences of this uprooting on local communities. Or we can ask those who decided to stay.

‘Subsistence lifestyles have given way almost entirely to money economies and wage-based employment, which the villages lack’, says Zapotec activist Aldo Gonzalez, dialling in from Guelatao de Juarez, a town in Oaxaca’s pine-pitched northern mountains. Since the 1950s, ‘the local government-funded schools, armed with development-based directives, have seduced young people into the cities, into jobs, far away from their people, their culture, and the milpa.’

‘These travels,’ he continues, ‘cultivate certain expectations within the community. The young people grow up with the rumours from fathers, uncles, and cousins of “a better life” in Los Estados Unidos.’ They see the privilege and prestige associated with making dollars and being able to feed one’s family from abroad, and run with it. In the face of worsening poverty and violence, ‘the only way forwards surfaces as the road out of the village.’

When the work is seasonal, migrants often return home to a hero’s welcome, cash in hand. ‘This contemporary rite of passage is seen as a source of honour for the workers, their families and the village.’ However, ‘few confess to the hardships they face abroad, while fewer still are present enough to see the effects of their departure unfolding among their people.’ This can keep one’s pride intact, but what does the preservation of pride cost the collective vision of the village? For Aldo, it means an inability to foresee the intergenerational consequences of one’s movements.

The causes of forced migration are many: drought and hunger, natural disasters such as flooding and earthquakes, as well as war, conflict, and poverty. In Oaxaca, these catastrophes have long been coupled with territorial disputes between villages, as well as industrial megaprojects that manufacture division and violence. As Aldo explains, ‘a degree of hopelessness takes hold, usually followed by an exodus. Communities deteriorate, either into de facto offices for multinational corporations, sites of civil war or ghost towns.’ Without cultural roots sustaining the local soil of place, resistance becomes a hope rather than a skill.

I remember: what I found in the Macedonian Old Country was a place defined by barbed wire, border fences and exile. No longer a village. And there, the last of our babas, tending to the memory of place, mostly alone.

The Right to Not Migrate

By June 2009, the writing was on the wall. In the rural Mixteca region of Oaxaca, in the town of Santiago Juxtlahuaca, far from the state capital, a three-day assembly was held by the Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales (Binational Front of Indigenous Organisations, or FIOB). Hundreds of Mixtec, Zapotec and Triqui farmers attended, some accompanied by their migrant kin. Together they began to debate the long-term consequences of their movements on and with the families left behind.

The migrants spoke of how ‘many of the problems they faced in the village were often worse in their new, northern homes: harassment, violence, substance abuse, and indigence.’ David Bacon, a labour rights activist and author, documented the assembly and its fallout. ‘Their farming families reflected on how some of their people, either deported or returning home voluntarily, sometimes brought these vices home with them, to places where they hadn’t previously existed.’ Addiction to alcohol, drugs and new technologies. ‘Cultural erosion’, as Aldo Gonzalez put it.

Contending with the causes and consequences of their own movements, while reinforcing the right to migrate, the men and women in Juxtlahuaca ‘repeated one phrase over and over: el derecho a no migrar – the right to not migrate.’ Or ‘the right to stay home’, as David translated it in his book by the same name.

‘The decision to migrate must be a choice, not a necessity’, says Bernardo Ramirez, former FIOB organiser and current president of San Juan Mixtepec Distrito 08, a town within the Juxtlahuaca district. Since the declaration, locally organised and operated projects have been implemented in different regions of the state to promote these rights, ‘to find better ways of living within one’s place’.

Bernardo listed local agriculture and aquaculture programs that employ young people, some of which were started by returned migrants. These include ‘edible mushroom and blackberry cultivation, trout farming-based ecotourism endeavours, and the greenhouse production of local cash crops.’ In some cases local microlenders help fund new projects at little to no interest, ensuring that the money stays in the community. While migration northward continues, Bernardo explains, these new grassroots enterprises are creating ‘dignified work’ within the communities, re-rooting people in place.

In the Sierra Norte, Aldo Gonzalez details wage-paying jobs that regenerate not only local practices of milpa farming, but also communal governance and craft traditions, each of which has been compromised by emigration, the desire for money, and increasingly hypermobile media. ‘We focus on education programmes seeded to reclaim indigenous identity, to re-member local languages, culture, and ancestry’, all of which have been denigrated for generations by government- funded curricula. ‘Since schools have been, historically, the primary tool used to condemn indigenous self-worth and replace it with the “progress” of modernisation and out-migration’, that is where they now aim their arrows. ‘If you understand the value of your culture, you wouldn’t be so quick to leave it behind’, he concludes.

I remember: breaking bread in this baba’s kitchen. She spoke my grandparents’ dialect as we exchanged family photos taken on different continents, in different eras, tying then to now, here to there, and me to her. We tried, mostly in vain, to marshal a mosaic that held everyone together. A photograph without borders.

Mainstream Myopia

UCLA professor Dr. Gaspar Rivera Salgado was a key part of FIOB’s operations in previous decades. Asking him why the right to not migrate hasn’t yet become a viral movement, either within the villages or internationally, he explains how regions like the Mixteca continue to exist under the constant threat of violence. Community groups commonly organise as armed ‘land defenders’ but often devolve into paramilitaries and narcotraffickers – the very things they originally sought to protect their people from.

Gaspar was clear: ‘For political transformation to take place, people can’t be killing each other.’

The histories and circumstances of each place are unique. How migration and displacement visit themselves upon such places is also unique. In regions like Aldo’s and Bernardo’s, local resistance projects are thriving, while in others they have failed. The struggle continues: between the right to migrate and the right to stay home. We can ask if the slow uprooting of the coil of comunalidad – the collective braiding of people to place – contributes to increased insecurity in these villages.

In the United States, Gaspar reports, the right to migrate has become a sacred cow, something untouchable. Among leftists, critiquing immigration is seen entirely as acquiescence to xenophobic right-wing agitators. Any demonisation of migration must be met with migrants’ deification. Activists refuse to realise that, in Gaspar’s words, ‘migration is part of globalisation … an aspect of state policies that expel people.’ We can wonder about the negation of nuance, and whether it prevents us from properly contending with migration’s consequences, not only in the places migrants move to but in the places they move from.

Within mainstream discussions on migration, there is a marked lack of consideration for the places and people migrants ‘leave behind’. The first global study ever undertaken to investigate the issue of migration on the wellbeing of those who stay was only published in 2018. In Mexico, the study detailed ‘greater feelings of resentment and depression among children of emigrant parents,’ as well as ‘increased sadness, crying, and difficulty sleeping among the stay-behind mothers.’

I remember: waiting in her garden for a taxi back to the city. I stuttered farewells in a foreign tongue, unwittingly echoing those of her people before me. Our people. As the gratitude and goodbyes subsided, I leaned in to offer her an embrace. She drew closer, and as she did, she began to weep.

The subject of remisas (remittances) – money sent home from migrant workers – took centre stage in this study as a significant part of the Mexican economy and the villages that depend on them, accounting for a 2% increase in ‘life satisfaction’. However, the authors concluded that ‘while remittances “buy happiness”, they do not relieve the pain of separation.’ Instead, they function as what the study referred to over and over again as ‘compensation’.

For those who choose not to migrate, these funds can offer a sense of financial security. Such security, however, remains contingent on the precarious labour, trade, and border policies of foreign nation states. As migration increases, so too does the relationship between the village and global capitalism. What it endangers is the collective autonomy conjured by the mutual aid of people who don’t always have enough. As Bernardo says, ‘In the fields, there is abandonment.’ Migration is a gamble that speculates on futures far from home and futures often contingent on bankrupting home.

I remember: the wet cracks in her voice as she mourned the emigration of my grandparents, of my father and uncle, to Canada. She lamented the absence of her children, of their departure to Germany. And now me, there, temporarily taking their place as the next-of-kin to leave. Then she began to keen.

In these villages, what is at stake is nothing less than the axis mundi, the centre of everything that weds people to place. Those who choose not to migrate recognise this. However, by the time they do, it’s often far too late. Home has already become the locus of loss. And the question remains: can we be responsible for a place by being elsewhere?

Migration’s Mythos

Half a century ago, around the time my family left Aegean Macedonia, John Berger began documenting the dilemmas of migrant workers within Europe. In his book A Seventh Man, he illustrated economically impoverished Mediterraneans moving north to France and Germany, contending with the same back-breaking conditions and ill treatment that we associate with migrants today. Berger insisted that we understand the need to emigrate within the context of a global economic empire, what he called ‘neo-colonialism’. How migration is caused by and feeds the system is paramount, but that system is also fed by history and myth.

In the United States, for example, the migratory mythology of the nation revolves around ‘pilgrims’ arriving from afar and searching out a better life. Over time, that search evolved into the settler-colonialism of ‘manifest destiny’, a God-given right to move and maraud. Today it’s referred to as freedom of movement (highways, car culture and tourism). Moreover, the republic founded on slave economies continues to be subsidised through the use of foreigners as ‘cheap labour’.

In Mexico, legend has it that the Mexica (Aztecs) inherited an origin story of people leaving their northern homeland, Aztlan, in search of a new one, eventually settling in Tenochtitlan, which today we know as Mexico City. The Mexican mythos emphatically marks a migration across the desert toward a more prosperous life, but also toward subjugation. The name of the nation itself carries and conceals a history of diaspora that in no way appears to be past. As Gaspar says, reflecting on the migrant path, ‘You travel with your whole history on your shoulders.’

The Nuances of Roots

As with our myths, we can look to language to track our tribulations. How does the language of rights overshadow the effects that migration has on the places that are left behind? How might this language enthrone the individual and estrange us from our ability to live communally?

What if the right to travel, even the right to migrate, undermined a collective responsibility to home? What if every new person in flight meant one less with the ability to respond to the needs of the neighbourhood? And what if that became the status quo, underwritten by the twinned myths of migration and conquest?

During World War II, the philosopher Simone Weil was asked to reflect upon the ongoing Nazi occupation of her homeland, France. Contending with the horror that had come to pass and how it might be averted in the future, she wrote The Need for Roots: Prelude Towards a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind. In it, she noted the distinctions between rights and responsibilities. The latter she refers to as ‘obligations’, a word that has its roots in the proto-Indo-European leig, meaning ‘to bind, to tie’, from which we get the words ‘ligament’, ‘liable’, ‘liaison’ and ‘ally’.

An obligation is a relationship of both remembrance and repair – an ability to recall how our bonds have broken and a path toward their reparation. To oblige is to weave anew that which has become disentangled, to root once more that which has been displaced. When migration isn’t forced, could the right to not migrate be understood as a responsibility to stay home? An obligation to commune in the places we live and among the people we live nearby, but rarely with.

Today, rights are often promoted by the state and activists alike not only as universal but natural, inalienable. They are granted principally to the individual rather than the community, meaning the latter is presented as subservient to the former. This can easily obscure the obligations we have to home, to create the conditions by which people can move with dignity and autonomy. What if the question went beyond a right to travel or a right to stay home, toward an understanding of how deeply rooted in our places we might be?

The people who declared ‘the right to stay home’ or ‘the right to not migrate’ 15 years ago in Juxtlahuaca understand this. They refuse to ignore the lived memory of what emigration can do to a place, to those who choose to stay, to the loom that weaves culture, language, soil and soul. In the small ways that they can, they’re affirming their rights as responsibilities, rather than employing the former to evade the latter.

I remember: walking around her village, passing the abandoned buildings and the shuttered cemeteries. The term ‘ghost town’ reverberated over and over in my mind. But in the rear-view mirror of the taxi, watching my teta-baba’s face fade into the distance, the haunting revealed itself. The village was not dead. It was not gone. And yet, I had summoned and seen it as such. I had taken my place in a long line of kin, whispering ‘so long’ in this elder’s ear at the edge of the village. An apparition, vanishing as quickly as he appeared.

A Better Life Includes Mercy

I myself am a child and beneficiary of migration. For some, the memory of movement prevails in the stories and sentiments of older generations, of those who undertook the journey and those who chose to remain. For many others, there is no memory. At some point, ‘how we got here’ and ‘why we had to leave’ collapses into ‘a better life’. Whether it arises from the refusal to remember or from the passing of time, amnesia appears to define how we understand migration today.

I write these words remembering the tears of my teta-baba, imagining those that score the faces of the women and men in the villages here in southern Mexico, facing the same heartbreak. Their grief is not new. It erupts as a pattern language, the secret longings of a century that refuses to end. Chances are it hides there too, in the wrinkles of your people.

I remember: what I left her village with that day was not confirmation of ‘Old Country’ glory, not a retrofitted, ancestral identity, nor proof that your people can go back to where they came from. If there was anything to write home about, it was the sorrow stamped on my chest like Rorschach inkblots, the map of a village, dismembered.

Migration is not inherently misguided, natural or even noble. Often, it is the only option. When flight promises more food than the field, movement indelibly marks people and places with desertion.

At the same time, to ignore how migration feeds economic slavery and culture loss is to reinforce the belief that there is no other option. It is to codify exodus as imminent.

When it isn’t, when the act of staying home ripens by seeding home anew, the axis mundi – the crucible of community – can be fertilised, fed and fortified. That is, of course, when migration remains a choice.

P.S. My Chinantec friend never made it to Canada. He did, however, manage to survive the long road north, back to his migrant community in the USA. For now, I live closer to his family as he does to mine, without any guarantee that we’ll ever see them (or each other) again.

This essay was originally published in Dark Mountain Issue #25 (2024). You can purchase a copy and lay your eyes on the other provocative offerings here.

What an illuminating and heartbreaking post. I really enjoy your ability to share in such a deep and heartfelt way, without offering concrete solutions… the questions you leave us with are the bitter pills of our current worldwide predicament. This morning this video showed up in my inbox. You mentioned how schooling plays a role in the “better life” thinking of migrants, and it occurred to me that alternative “unschooling” could play a part in raising children to feel a tangible connection to place as well as the skills to have a better chance of “staying home” throughout their adult lives. Thank you again for your sharings. Here’s the link to the film: https://youtu.be/gryGA0Wm97M?si=io6gi8UZkclLYH22

Blessings to you Chris!

There is a drawing exercise that I got the first years to do in art class, and it is 'to draw a house' and 'draw a home', on a sheet of paper, in x6 iterations, under a timer. It's always an interesting experiment to gauge how our imaginations of the house/home - is based on early childhood learning.

I'm not so sure about 'the right to' as a framing, especially when all sorts of demands of 'rights-based' wants are too pervasive. I think I prefer the notion of 'the sacred obligation to make home', which isn't anchored on where as such, but more with whom.

For there is also a destiny to the stories of people, and the gods, in their co-creations.

And maybe, we move, because as humans, our experiences move us.

And we are still a herd species.