The Tiger and The Firefly | QMM #8

Even in the Rainforest, Digital Connection Invites Consensus, But at What Cost?

BREAKING NEWS: , in association with Gray Area SF, is resuming his Understanding Media Intensive in January 2025. If you feel provoked or paralyzed by the times, I implore you to take this course. It will provide you with clarity, tools, nuance, depth, breadth, humility, really smart fellow students and most importantly, the skills you didn’t know you needed. All details can be found here: https://grayarea.org/course/andrew-mcluhan-teaches-understanding-media-intensive-part-two-2025/

Quixote’s Media Meditation’s #8

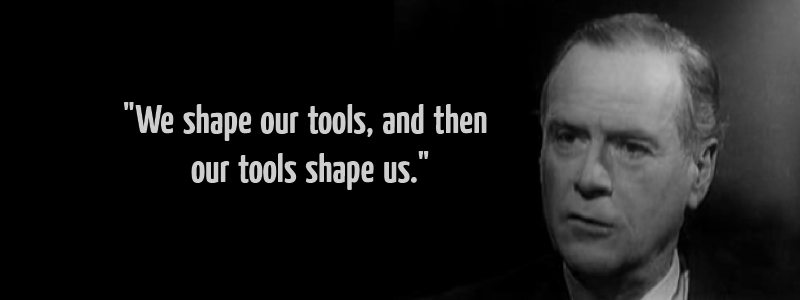

Assignment: “Today, when we have extended our bodies and senses by technology, we are haunted by the need for an outer consensus of technology and experience that would raise our communal lives to the level of a worldwide consensus.”

Are we there yet? Have we fulfilled that need by the internet? Or whatever you might imagine? And why or why not?

Three generations ago, when Marshall McLuhan was writing Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, it was still possible that the trajectory of our tools could both deepen our shared understandings of the world and broaden them. That is, if media ecology was present, palpable and promoted. Three generations on, that trajectory has shifted greatly and subsequently shafted our ability to do anything about it. Today, most of us live and suffer the absence of media ecology’s endowment.

The existential possession (or extended dissonance) that Marshall noted more than sixty years ago has only worsened. The result, I believe, is an inversion of what he called an “outer consensus of technology and experience.” Instead of our communal lives being raised or rewarded, they have disappeared entirely or become shells of their former selves. Instead of the quality of community defined by a more acute and reflexive relationship with our tools, the lack and loss of such relationships has undermined our ability to belong together. What we’ve been saddled with instead is a vacuous and calamitous form of globalization.

In McLuhan’s time, global economic imperialism was a process already fully underway, one priming its engines for total eclipse. Of course, today, we live in the long twilight of this tumour, blasted unceasingly with radiation just to keep it alive another day.

Contending with how it came to be this way, with how our tools failed us and how we failed our tools, we might look to countless intervening intermediaries such as highways, airplanes, television, radio, the computer and cinema. Instead, I’ll offer you a story regarding the infrastructure that inoculates against community – the internet signal or WiFi and its globalizing impulse – so that we might wonder how wide we’ve been worlded.

The Foreigners and the Fireflies

A little under a decade ago, I began working alongside indigenous Chinanteco farmers in southern Mexico. In one sleepy little village, there is a rocky river that swims parallel to the single, two-kilometre-long road. Between them lie the homes of the three hundred-plus people that inhabit the pueblo.

Beyond them, in the mostly vertical jungle on either side, grows the materia prima of the local economy, including the legendary cacao trees, one of whom is referred to as dsieg lag (in Chinanteco) or cacao tigre (in Spanish). Tiger cacao. As far as the outside world is concerned, there are no tigers in this part of the world. Nonetheless, it remains revered as the community’s totem or guardian.

To get there, one has to brave a five-hour van ride, passing endless mountain curves, that most confess would be easily mistaken for a laundry machine had most people ridden inside a laundry machine. Then, from a sweltering transit hub between cities, shared pickup trucks (colectivos) can take you to the village, climbing the extra hour through fecund forests to finally arrive, here.

This community has survived for centuries, if not millennia, including an intense, forced relocation in the 19th century. Living in a unique place such as theirs permitted the communal governance and fabric to hold. The river, the jungle and the human culture that arose from them offered the people, in reciprocity, everything they needed. Eventually, the promise of a better life swept many of the men onto the long northward road to Anywhere, USA. And yet, the social fabric remains taut, woven anew by the rest of the village.

On one of my annual visits, along the bumpy but beautiful jaunt up the mountain, a local man named Jose who I’d never seen before greeted me. “Que onda, wero. Where are you from? What brings you here?”

Hearing this arise without a thick, Hispanic accent is usually a sign that, so far from the nearest city, this man had probably spent time in Gringolandia. He was friendly, excited to see a foreigner on this ragged, rural route. We got to talking and he explained how he recently returned home from El Norte and set up a satellite dish in the village that provided WiFi to the residents. Proud with proof in hand, he graciously offered me a handful of fichas - paper tickets or admission to an hour-long internet fix, whenever I wanted.

Now, while the remote revolution is happening at a meteoric rate in places like this, something about it still surprised me. During my first few trips to the village, internet access and even cellphone signal required a trip down the mountain.1 It was still a living example of what a place looked like without being entangled in the world wide web. All of that was about to change.

On the second night of that stay, after a long day’s work in the parcela, I quietly left the house to send an email. I walked up the grassy embankment to the newly paved road and entered the ficha user number and password. Waiting for the signal to connect, I looked up and around and noticed in the darkness, a firefly in the distance.

I squinted, blinking back and forth before realizing that light was pouring from my phone. I turned it off momentarily and readjusted. There, down the opposite side of the road was another luminescence. I blinked, squinted and realized a deeper darkness was required. When my eyes finally adjusted, I realized what those fireflies, those nocturnal anomalies, really were.

Dotted along the single-lane road of this village, were people. Like inland ports of call, they were all fixed with their own little lighthouses. I stood there, joining them, each surrounded by the spectre that we were being carried by our phones towards “a better signal.”

In my years there, I had never seen such a thing. I had never seen people on the internet, period. And suddenly, the fireflies were usurping the striped, sentinel tiger on the local village throne. Under such light, it seems, we were evading the communal life inside for the private life on the flat screen.

Con-Sensus Reality

Digital technology re-places our seminally shared understandings of the world. Modern media extends our sense perception out beyond our bodies. While our intellectual explanations might suffice to render these schisms visible, the map is not the territory. Merely reading about our myopic minds on a screen is not going to subvert that myopia.

The modern separation anxiety between human and home that Marshall referred to as a “haunting” is the feeling - the felt presence - of belonging in our bodies. And yet, for so many, it is an ab-sense, a missing channel, a sense-ability that should be there but isn’t. Over the last seventy years at least, community and consensus have been outsourced. What we’re sold in its place is certainty - an exploratory and explanatory balm to get on the other side of our technological pain.

The promise of a “worldwide consensus” has already come to pass, not in terms of the content of our conversations, but in terms of their contexts. It means little anymore whether one is a liberal or conservative, ascetic or transhumanist, pro-war or anti-abortion when the dominant discourses have irredeemably undermined the ability to imagine the world beyond those ideologies. It doesn’t matter what your answer to the question is, as long as it’s recorded and diffused on a glass (or crystal) screen. (No, the irony is not lost on me).

Consensus, here, is the collapse of diversity and difference. It is, as the Oxford Dictionary points out, “the agreement in opinion, feeling, or purpose among a group of people, especially in the context of decision-making.” In our time, consensus is not, as the word’s anatomy indicates, “a bringing together or an intimacy of senses.” Neither is it the result of the ingredients of a people’s collective life being cultivated with care and commitment. It is, however, still an alchemical reduction, but one that turns the mixing into a monoculture. This is what I saw happening to the tiger’s sustenance over the last decade.

The virtual connection invites the contemporary consensus and the smartphone is the signal that seduces us into it, to be anywhere but here. It invites the villagers in the Chinantla into the illusion that their migrant kin are closer than they are and in so doing pulls each a little bit further from where they are. This is not to lay blame or assume that if we all just stopped moving the world would be a better place. It’s never that simple. It is, rather, to implore each other to bear witness to the minute and often mutilating changes that the trajectory of our technology induces both within and among us.

Today, as in the 1960s, we are extended, stretched out into and over a virtual utopia by which we are blended into bricolage. Our local senses and sentience, human and otherwise, are not quite recognizable as such in the smouldering cauldron of global similitude. We have reached a form of consensus, it seems, simply by virtue of our inability to de-screen. In that, we might be in agreement, but we remain haunted by an inescapable glow, by a ghost dancing in the distance, not unlike the beings of the Chinanteco forest.

These reflections on technology, language, media ecology & literacy are provoked by Andrew McLuhan’s mandatory, must-take Understanding Media Intensive. You can find out more about McLuhan Studies straight from McLuhan’s mouth by reading his Substack, here.

Typically, pueblos like this throughout Abya Yala (or the Americas) have long had a single landline that is used to receive calls. The operator answers and using a loudspeaker, he or she summons the recipient in the village. Think of the mobile pagers from the 1990s, except not mobile, and everyone knows you’re getting a call.

Much to contemplate here. Thank you Chris.